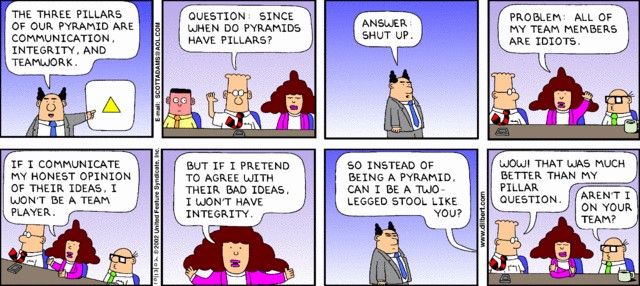

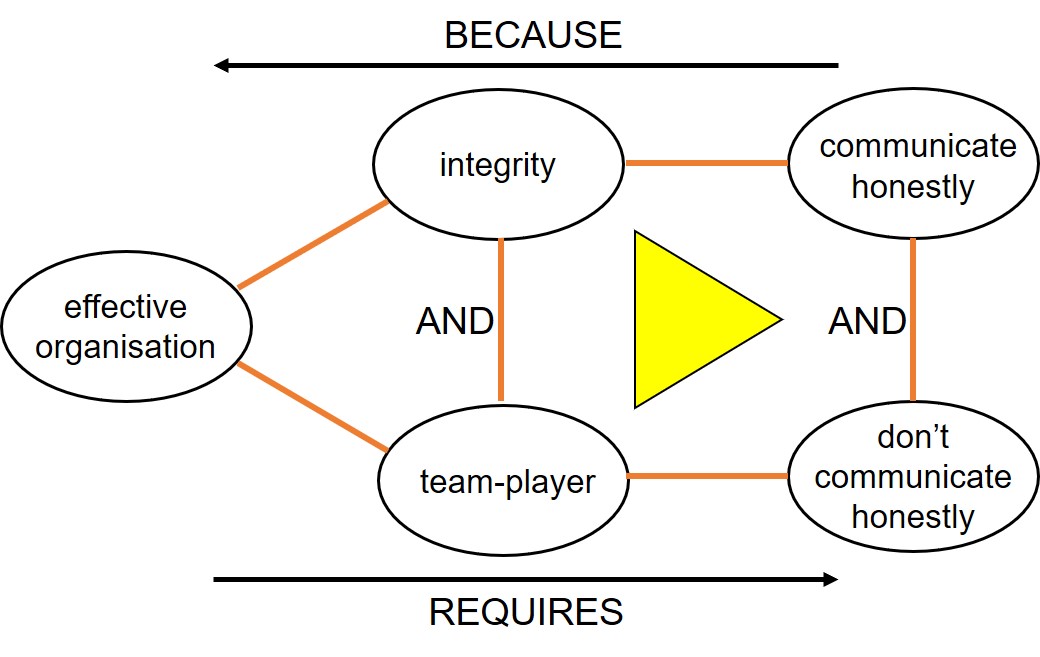

I love Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s work. I think I’d love it even more if he understood (or knew about) TRIZ. Or at least the concept of contradictions and our ability – should we give ourselves permission– to ‘solve’ and eliminate them.

I’ve been busy absorbing his latest epic, Skin In The Game, after I picked up my copy at his lektchur in London last month. As expected, it’s full of great insight and even fuller of (highly deserved) jibes at the Intellectual-Yet-Idiot (IYI) sector of society. By which he means economists, most academics, journalists, CEOs and all those other parts of society who make pronouncements about ‘the way things should be’ without having any skin in the game. Because they don’t have skin in the game, Taleb argues, they really don’t care whether their pronouncements are valid or not. In many situations, they win irrespective of whether they’re right or wrong with those pronouncements. Meanwhile, the rest of us who act on the pronouncements only to discover they were inappropriate, suffer asymmetrically. A classic example being former US Treasury Secretary, Rob Rubin. Rubin became a highly rewarded director and ‘senior adviser’ at Citigroup as it over-reached itself in the 2000s. When the bank became insolvent, Rubin didn’t write any check, but rather invoked (Black Swan) uncertainty as an excuse. Taleb comments, ‘nobody on this planet represents more vividly the scam of the banking industry. He made $120 million from Citibank. And now we, the taxpayers, are paying for it.”

As Taleb describes it in the book, there are two kinds of people, IYIs like Rob Rubin and people with ‘skin in the game’. Or, put another way, people who sound and look convincing yet talk nonsense, and people who talk sense but don’t sound or look the part. Skin In The Game describes the example of two surgeons to illustrate the point. One surgeon looks very smart, has all the right certificates on the office-wall and talks with great confidence to the patient. The other surgeon looks unkempt, has no certificates on the wall, probably doesn’t have an office and mumbles when they speak to you. Which one should you choose to operate on you? Taleb’s answer is that the in detelligent decision would be to choose the second surgeon. His compelling rationale being that the unkempt, mumbling surgeon has had to work harder to maintain their position than the smartly dressed surgeon. The unkempt surgeon has more likely spent their time devoted to being the best surgeon they can be, while the other surgeon has spent their time devoted to looking like the best surgeon.

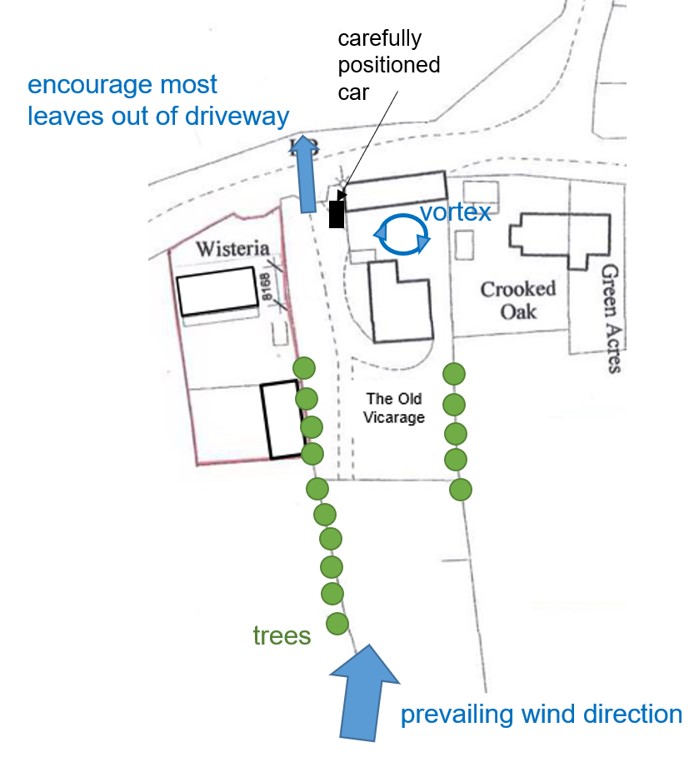

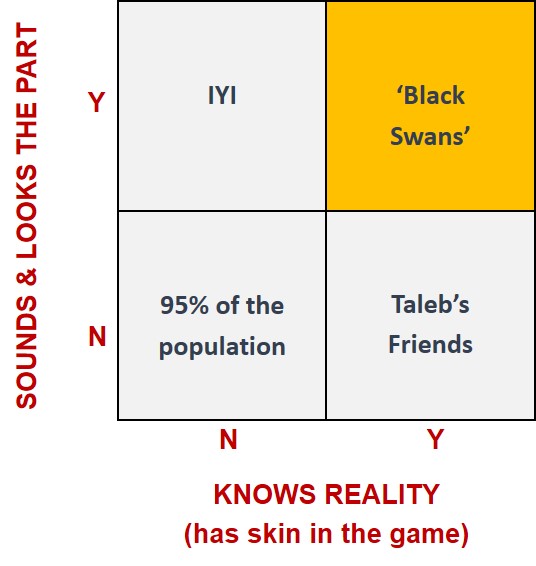

We can express the two-kinds-people-story on a simple 2×2 matrix. Something like this:

The horizontal dimension of the matrix considers whether a person understands reality or not. The vertical dimension considers whether the person looks and sounds like they know what they’re talking about. Taleb’s IYI class of people form the top left quadrant of the picture, and people with ‘skin in the game’ – people, in other words, who survive by knowing how the real world works – are contained in the bottom right quadrant.

Drawn as a 2×2 matrix, however, we see there to be not two but four kinds of people. The bottom left quadrant are people that don’t know what they’re talking about and don’t look the part either. I think this is about 95% of people on the planet. The more I look at what people write and say on social media the more I’m convinced this number is probably on the low side. And is probably getting lower.

But then there’s the top right-hand quadrant of the matrix. These are people that Taleb’s worldview doesn’t seem to acknowledge. These are people that know reality (and, by association, have skin in the game) and look and sound convincing. In TRIZ terms, these would be the people who successfully resolved the contradiction. In TRIZ terms life is specifically concerned with not accepting either/or dilemmas, and instead looking towards people who successfully switched to a both/and frame of mind.

I’m pretty certain Taleb doesn’t acknowledge such a both/and possibility. When I saw him lektchuring in London I’d have to say it was one of the worst presentations I’ve ever witnessed. It looked to me like he hadn’t spent more than ten minutes preparing what he was going to say, he mumbled, his most frequent word seemed to be an uncomfortable clicking ‘err’ noise, and he spent half the time fiddling with the copy of his newly published book, trying to find pages to read from, not finding them, and then moving on to another point, leaving everyone hanging halfway through his previous point. It was toe-curlingly bad. Part of me believes that Taleb has convinced himself that it’s not only okay for him to lektchur ‘badly’ (e.g. he now actively uses the self-depracating term ‘lektchur’), but that, like the mumbling-surgeon, its actively necessary for him to be bad in order to avoid falling in to the IYI category.

But this is surely a dumb assumption on his part. It is perfectly possible to solve the contradiction. He could have spent some time preparing his lecture. He could have bookmarked pages in the book that he wanted to refer to. He could have constructed some coherent anecdotes. But yet he chose not to do any of these things.

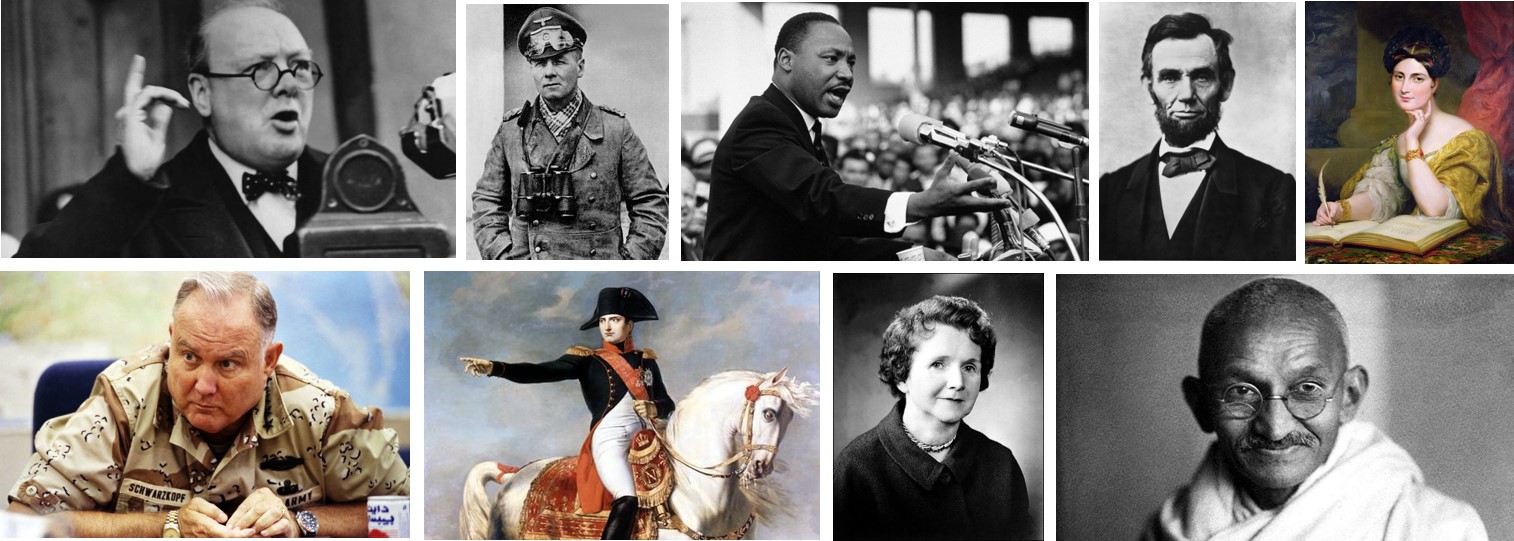

There are people who have solved the contradiction. Not many of them admittedly (inevitably since 95% of people are in the bottom-left quadrant of the picture), but we only have to think of people like Churchill, Rommel, Schwarzkopf, Napoleon (early part of career at least), King, Norton, Carson, Ghandi and Lincoln: people who knew that it was possible to solve the contradiction, solved it, and went on to deliver the best of both worlds.

Having skin in the game is really important. I totally get that. But that doesn’t mean I have to turn up to lectures ill-prepared. Taleb, I think, needs to understand contradiction solving far better than current evidence suggests he does. If he did, not only would Skin In The Game have been a better book, but he’d also begin to understand that ‘Black Swan’ events are merely revealed or resolved contradictions. And once he understands that, he’ll also come to realise that there are no such things as Black Swans. Only contradictions that society hasn’t solved yet. Or – more likely – didn’t have the foresight to go look for.