Life is negotiation. It is about what we ‘want’. And about other parties that want something different. Ultimately, therefore, negotiation is about contradictions.

I’ve spent quite a bit of time over the course of the last three years thinking about negotiation. Probably in no small part because it feels like I’ve spent the majority of this time watching the still-spiralling out of control debacle that is Brexit. The rising sense of horror that no-one in the negotiation – on either side – appears to be armed with even a modicum of creativity. Admittedly, of course, the EU side of the negotiation, having the upper hand throughout, haven’t had to be too creative, but even so, in public they have always talked about matters in terms of lose-lose, and how their primary job has been to minimise the losses on the EU side.

On the UK side, cemented by the Panorama documentary last night, the negotiating skills come across as misguided at best, and pitiful at their very frequent worst.

Ultimately, I’ve been left with the question, does no-one know how to negotiate any more?

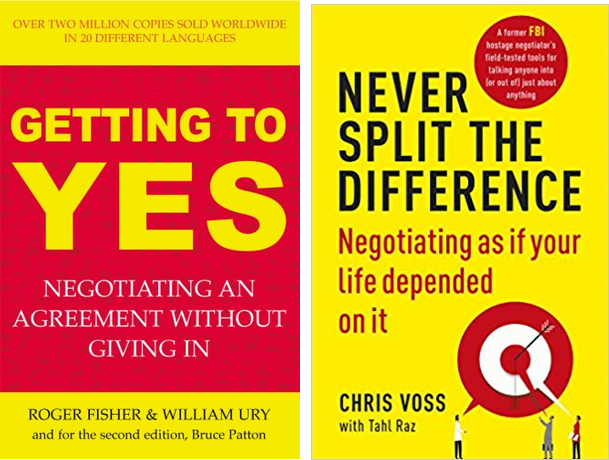

Last week I started reading Chris Voss’s book, ‘Never Split The Difference’. And unusually for any kind of book I read these days, it gave me an ‘aha’ moment. Voss’s book represents something of a step-change in the world of negotiation. All of the negotiation ‘classics’ prior to his book – think all-time classic ‘Getting To Yes’ by Ury & Fisher – are built on the premise that the parties involved in a negotiation are thinking rationally, and that negotiation therefore ultimately comes down to ‘problem-solving’. Voss’s innovation is an acknowledgement that negotiations are instead dominated by our ‘system 1’ emotional brain. People negotiate for two reasons, a good reason and a real reason, to paraphrase an aphorism we use a lot in Systematic Innovation world.

Voss’s book ultimately comes down to recognising the importance of our ABC-M model when it comes to thinking about what each party in a negotiation is looking to achieve. Its one of those blinding flashes of the obvious that has somehow taken fifty years, and Voss’s multi-decade career in the FBI to reveal.

It was inspiring to realise that ABC-M has been validated as a negotiating technique (‘someone, somewhere already solved your problem’), but more importantly it triggered another blinding flash of the obvious in my head.

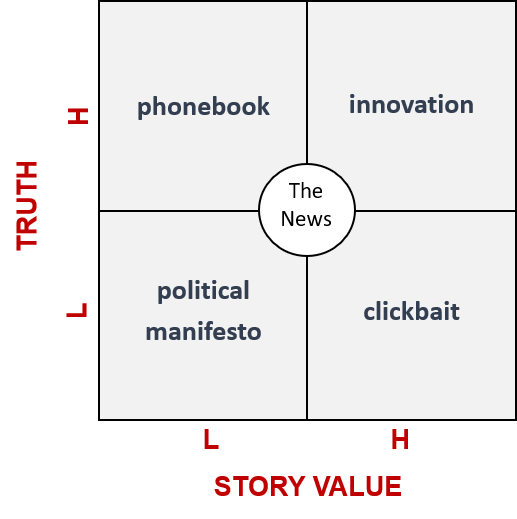

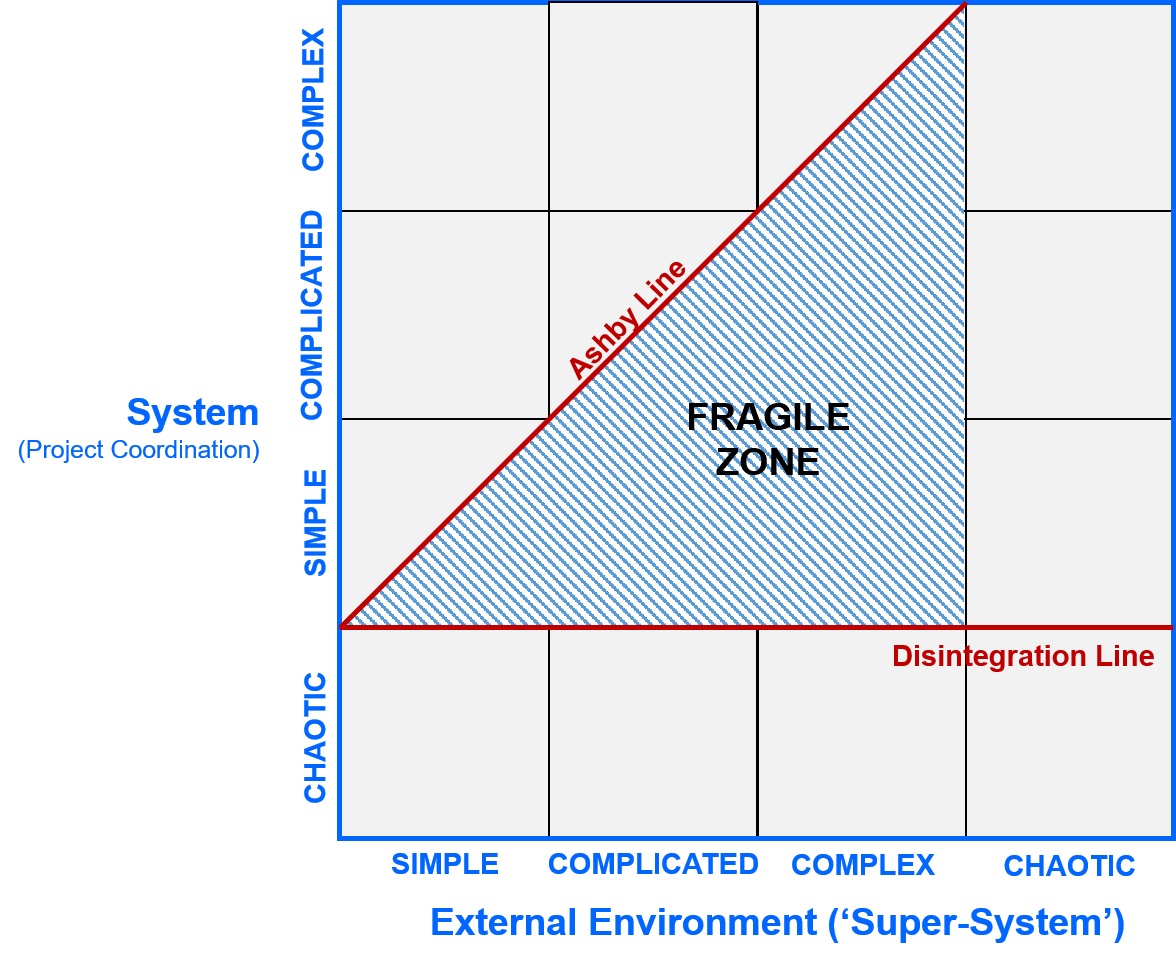

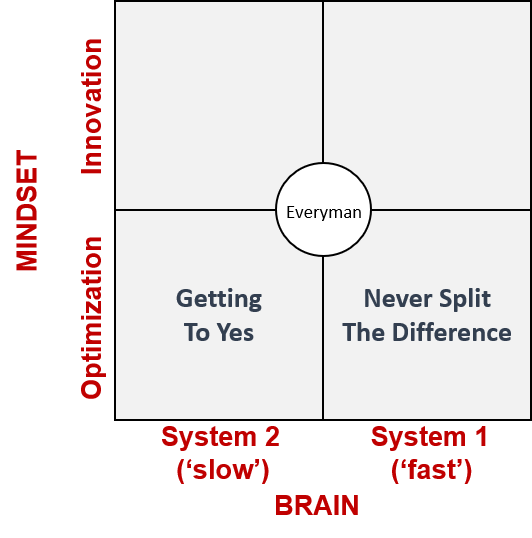

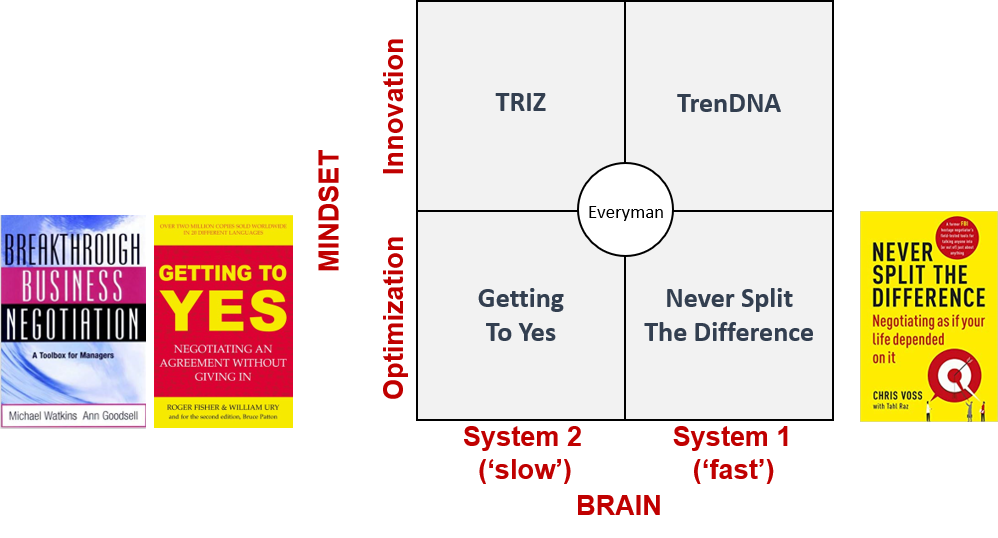

That flash started when I started to draw this 2×2 negotiation matrix:

Chris Voss made a jump into the ‘system 1’ emotional quadrant, but ultimately the solution strategies he ends up using once the other negotiating party has succumbed to Voss’s emotional ju-jitsu were still very much of the zero-sum, trade-off kind. Voss wins, you lose.

Which, I guess isn’t so bad if the person on the other side of the negotiation is a hostage-taking bank robber, but for something like Brexit, it can still only produce lose-lose or win-lose outcomes. No-one is going to come away from the negotiation having their cake and also eating it.

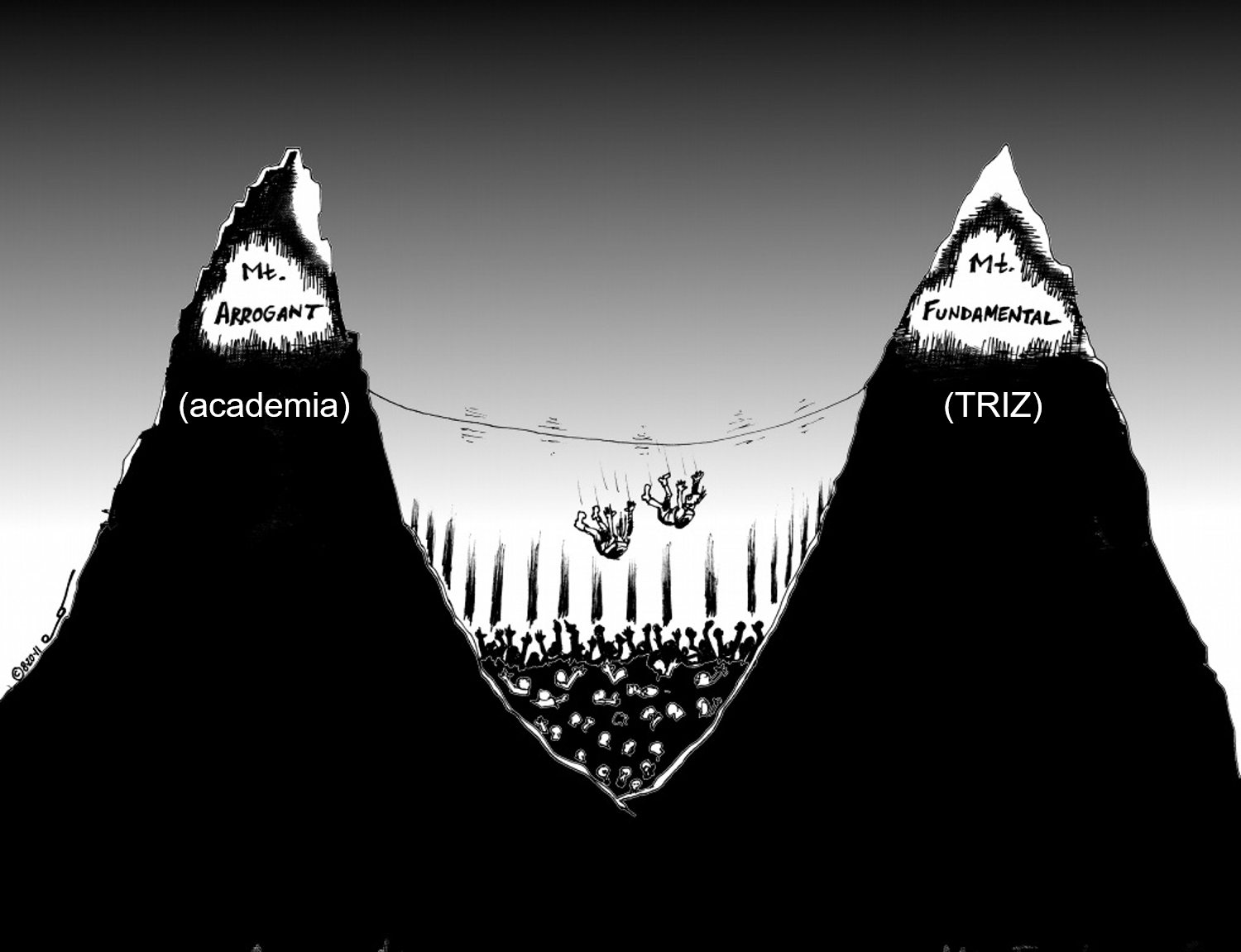

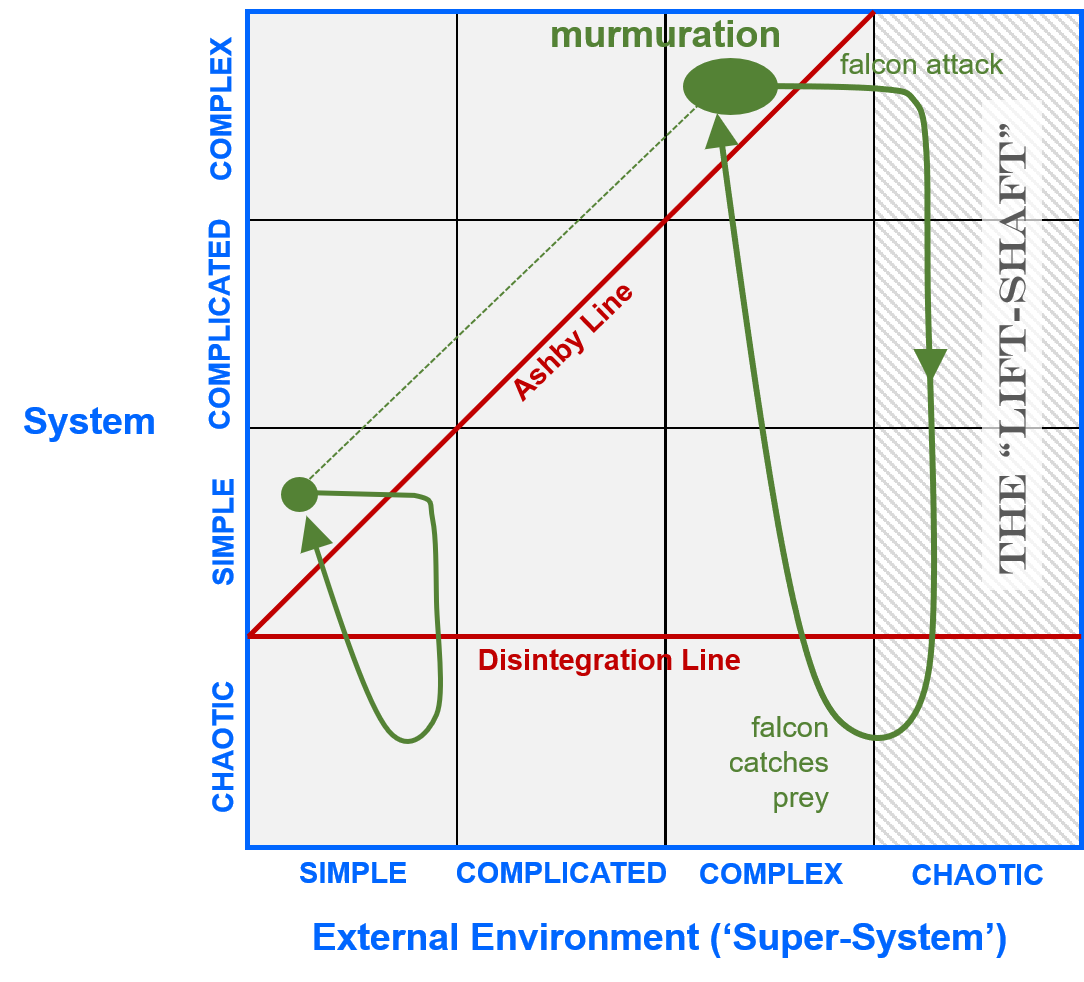

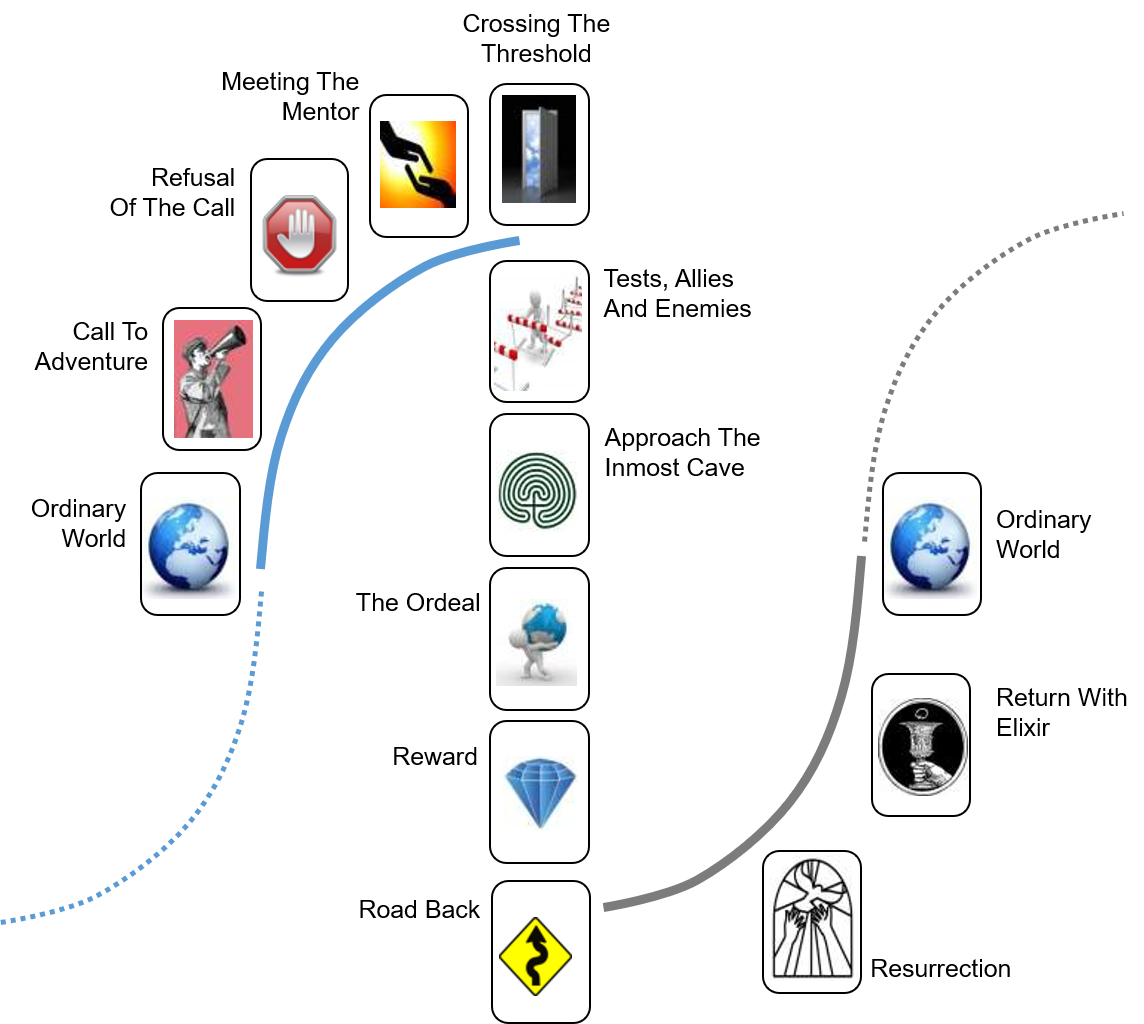

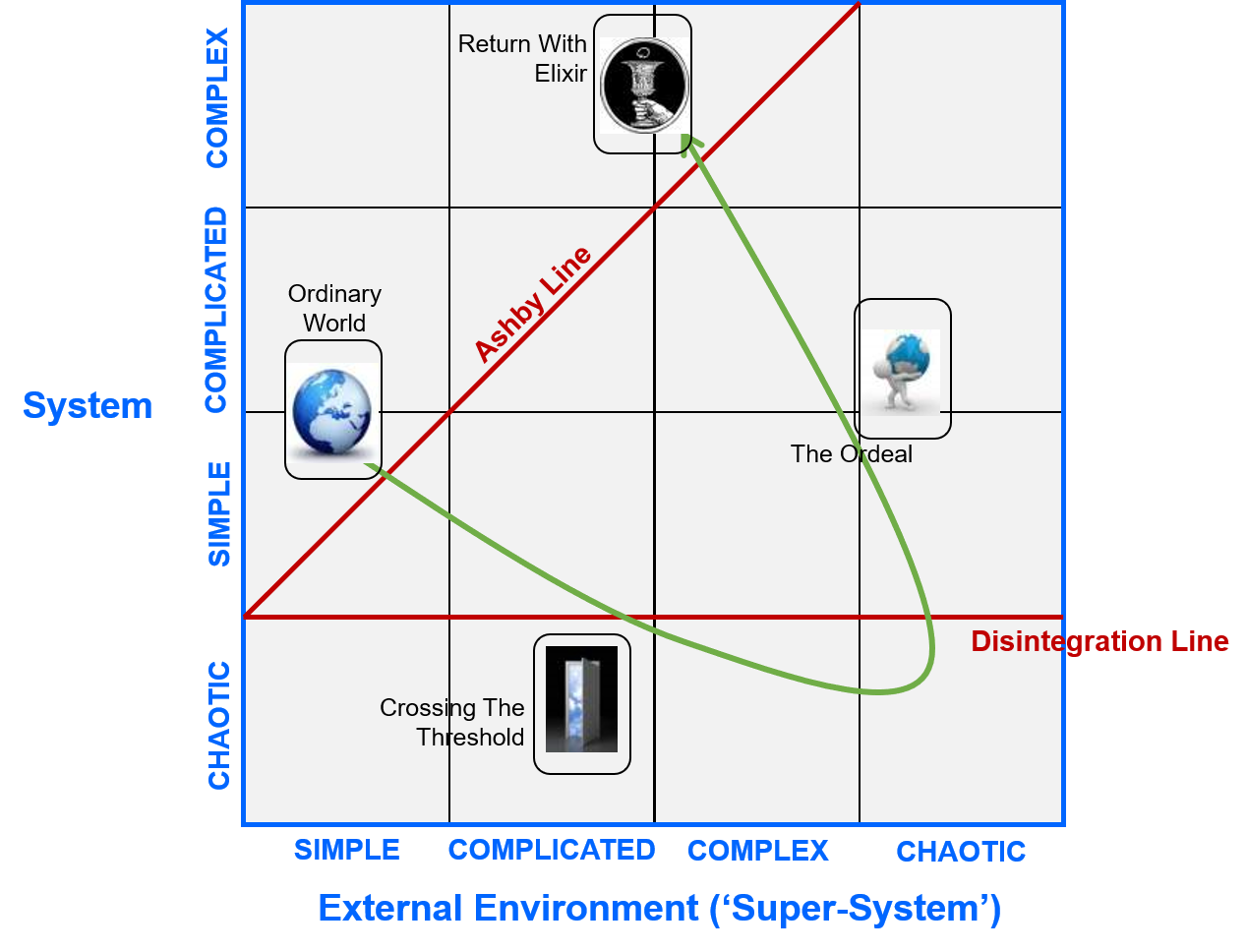

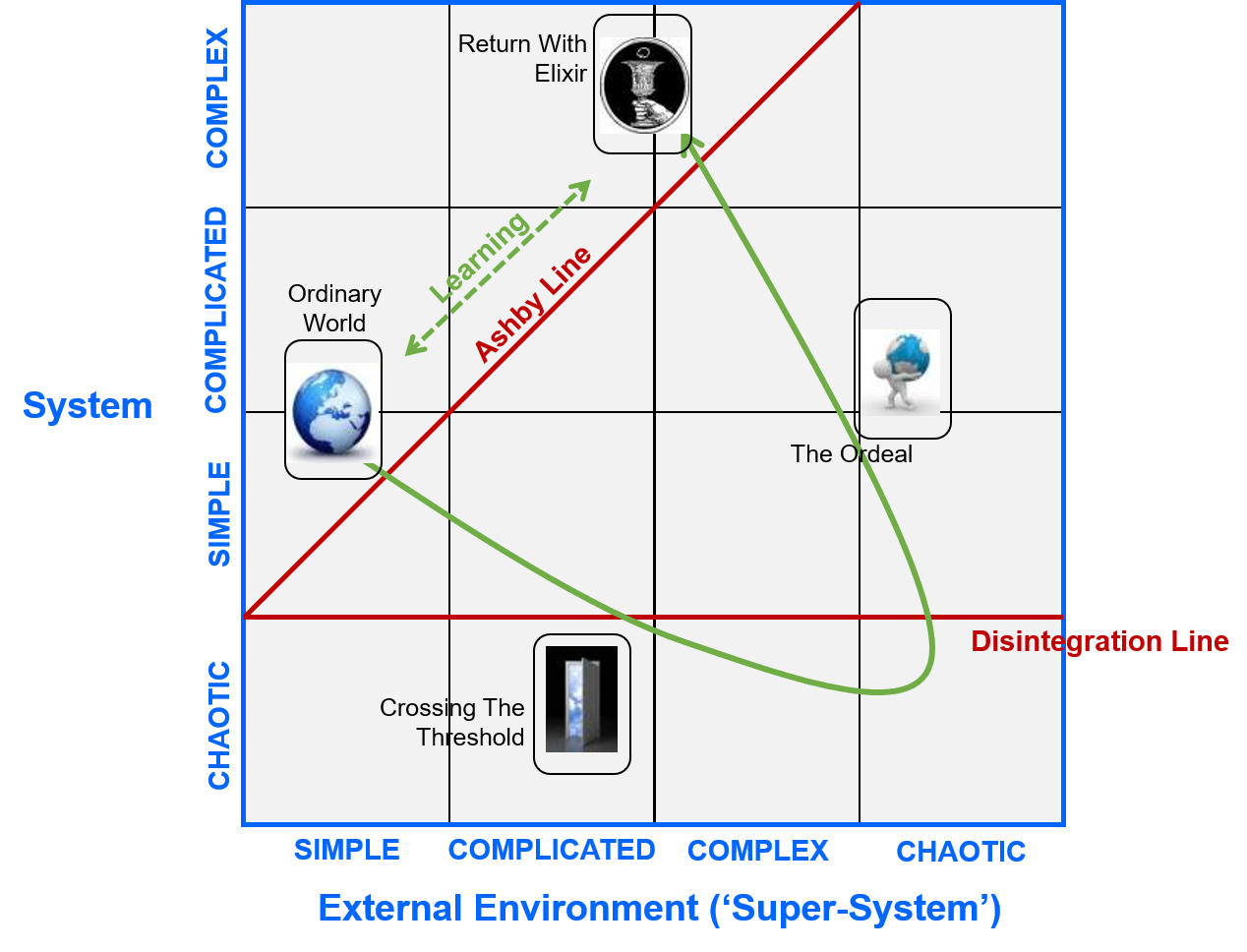

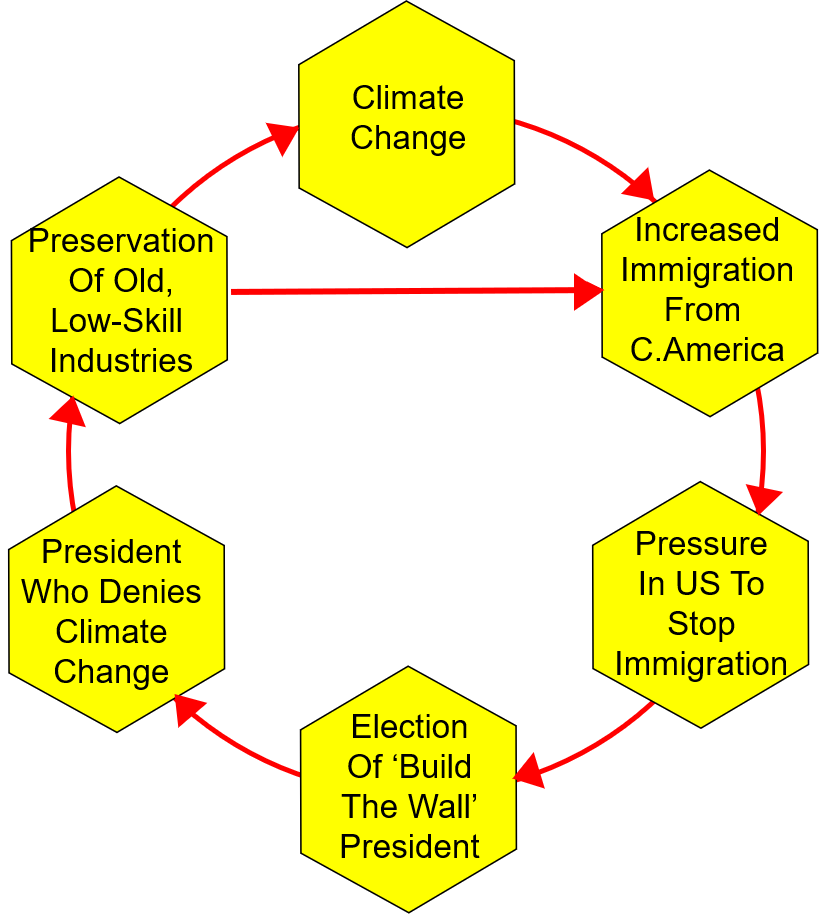

The only way to do that is to switch from an ‘optimization’ mindset to an innovation mindset. Negotiations are ultimately about contradictions, but truly resolving them – to deliver win-win – only happens when the contradiction is genuinely solved rather than assuming the answer inherently involves some kind of a trade-off. In this way, I’m pretty certain the next step-change in the shady, dysfunctional world of negotiation will be all about embracing the principles of TRIZ. And, if we acknowledge Voss’s findings, our TrenDNA research:

I think I can feel another book coming on…