I was reading Patrick Hoverstadt’s 2008 book, ‘The Fractal Organisation’ this week. Hoping it was going to turn out better than it actually did. The world of work requires more people understanding complex systems theory in general and Stafford Beer’s Viable System Model in particular, but no author, it still seems, has unlocked the formula that will get sufficient people started on the journey to make any difference.

In the end Hoverstadt’s book seemed more about making sly digs at corporate fads than making VSM seem more than abstract theory, but the section on measurement did at least trigger a thought that I think makes it possible to help teams to better understand the complexity landscape within which we are all operating. And if we can do that, we give ourselves a higher likelihood that we might end up being successful with our change efforts.

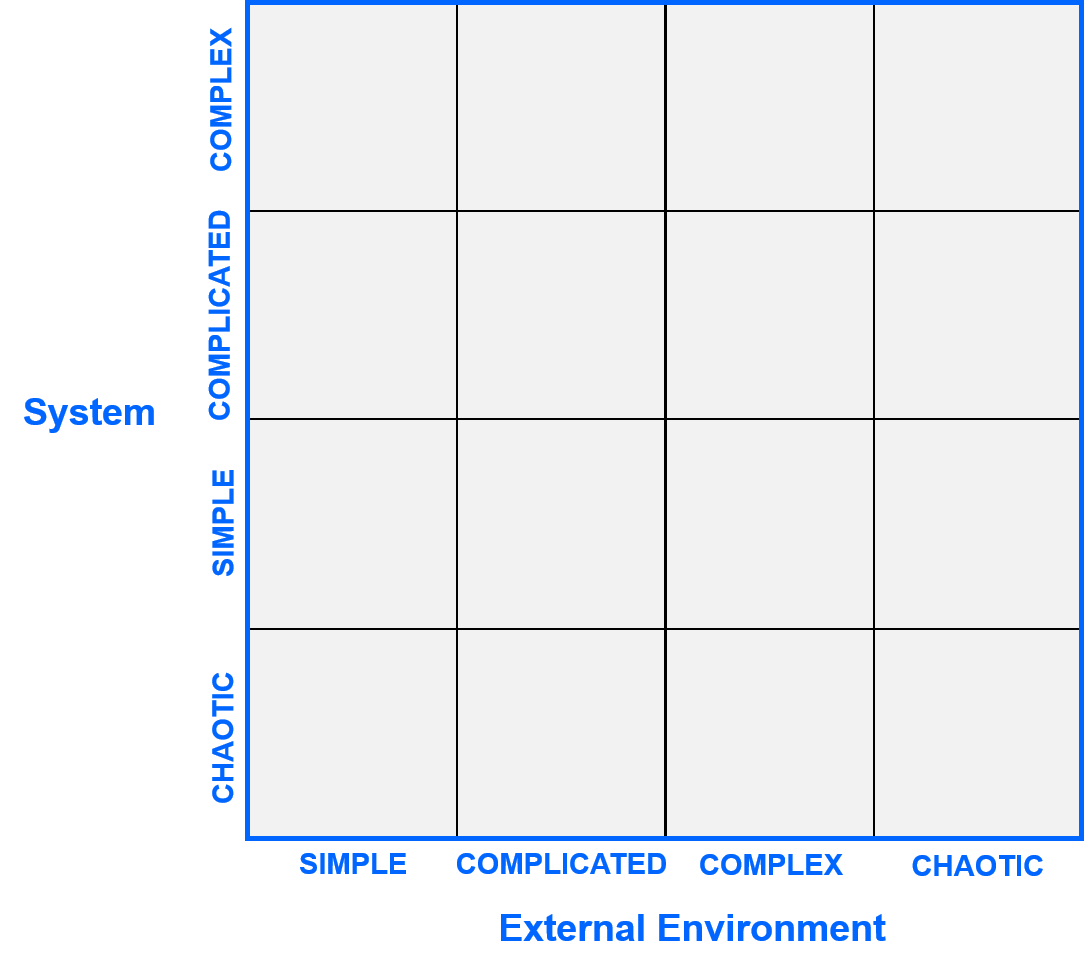

The start of the new complexity landscape model comes from a recognition that the manner in which a team might be operating may well be different from the environment that surrounds them. When I plot internal and external complexity as the two dimensions of a graph, I end up with something that looks like this:

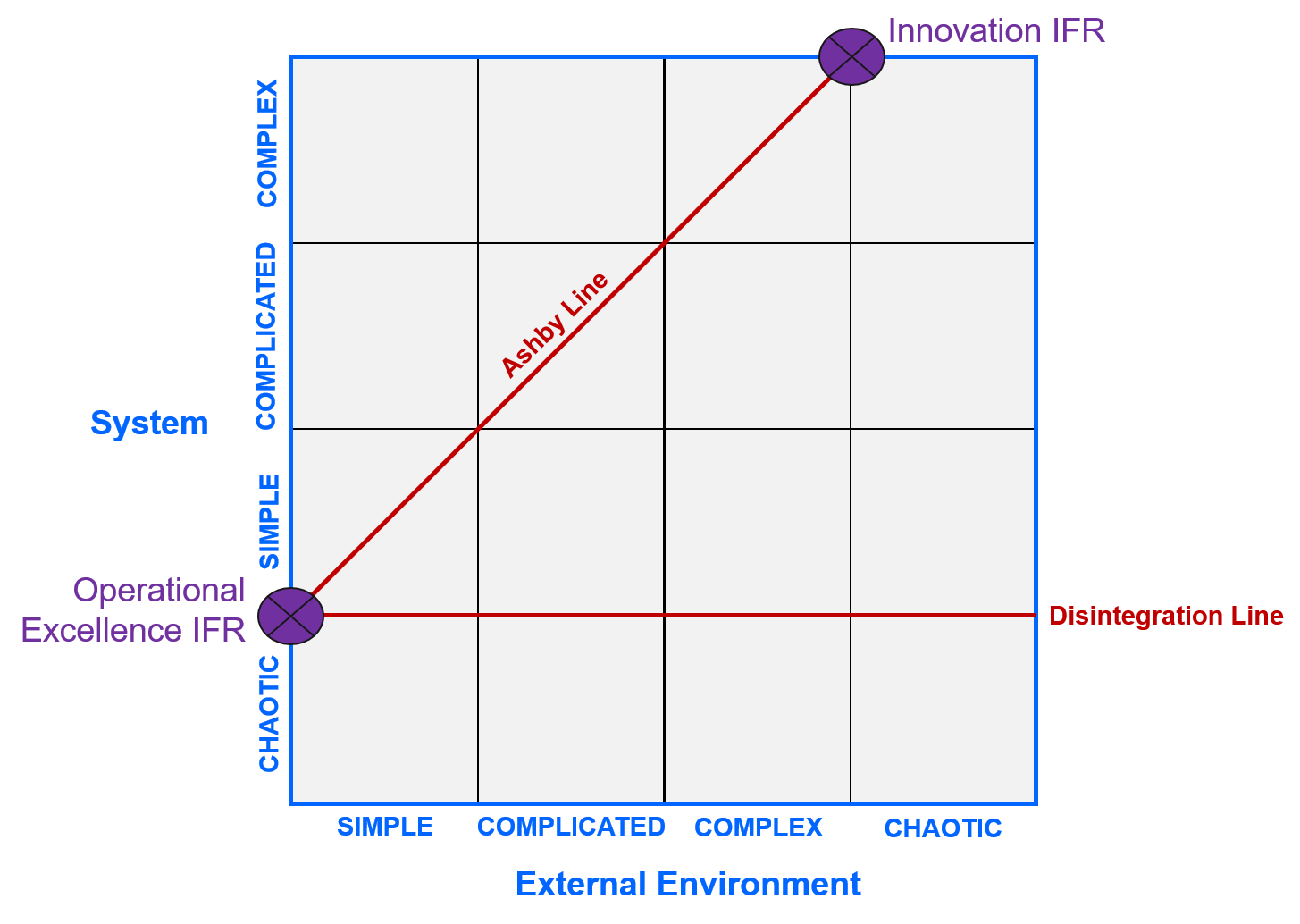

Both dimensions are split into the four basic types of complexity scenario that might be present: simple, complicated, complex and chaotic. Nothing magic in this segmentation model, it being pretty much the same as Cynefin, which in turn is built on the recognition that there is a discontinuous shft between each of the four possible states. I’ve labelled the horizontal external complexity axis as a spectrum in which the overall complexity increases as we travel left to right. For the vertical internal system axis, I’ve done something slightly different and placed the chaotic scenario at the bottom of the graph.

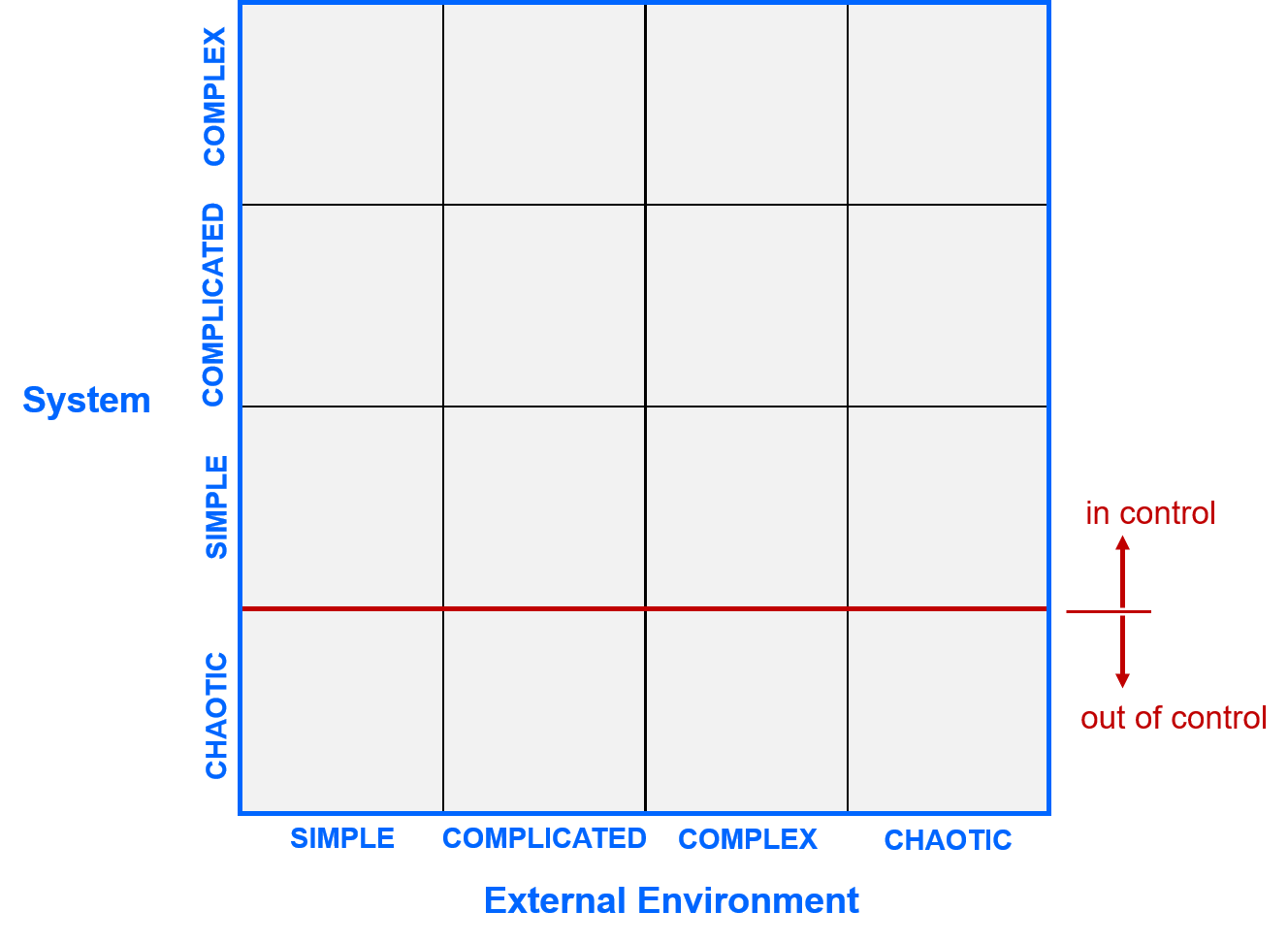

The reason for doing this is that when I add this line to the graph…

…I’m able to differentiate between ways of managing the system that are ‘in control’ and ‘out of control’. Below the axis line, the system is chaotic and out of control; above the line, we see the same simple-complicated-complex sequence as found for the external environment dimension.

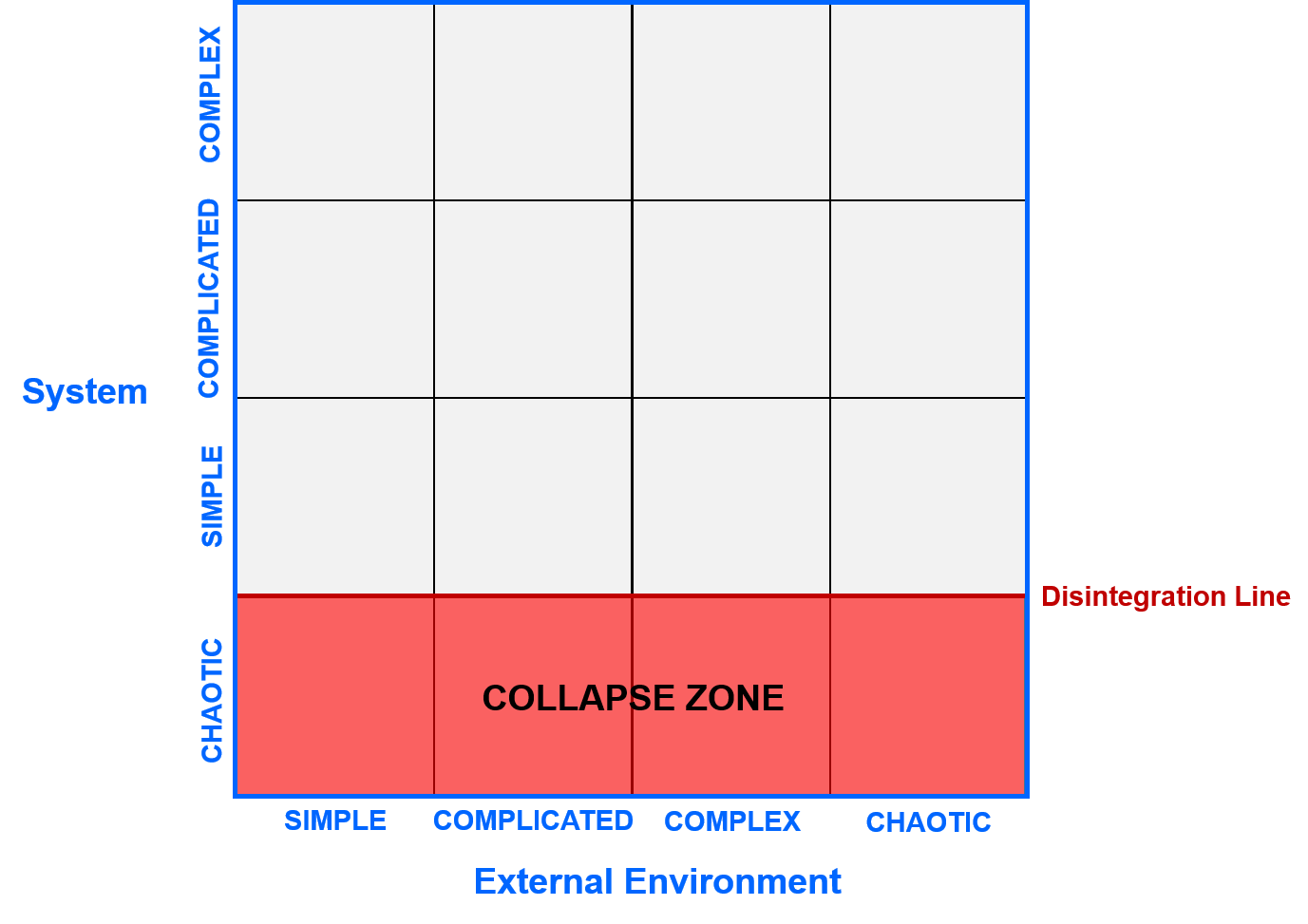

I can then describe the in-control/out-of-control boundary as a Disintegration Line, such that if I find myself operating below the line for any sustained amount of time (chaos can be really useful in short bursts), my system is very likely to collapse:

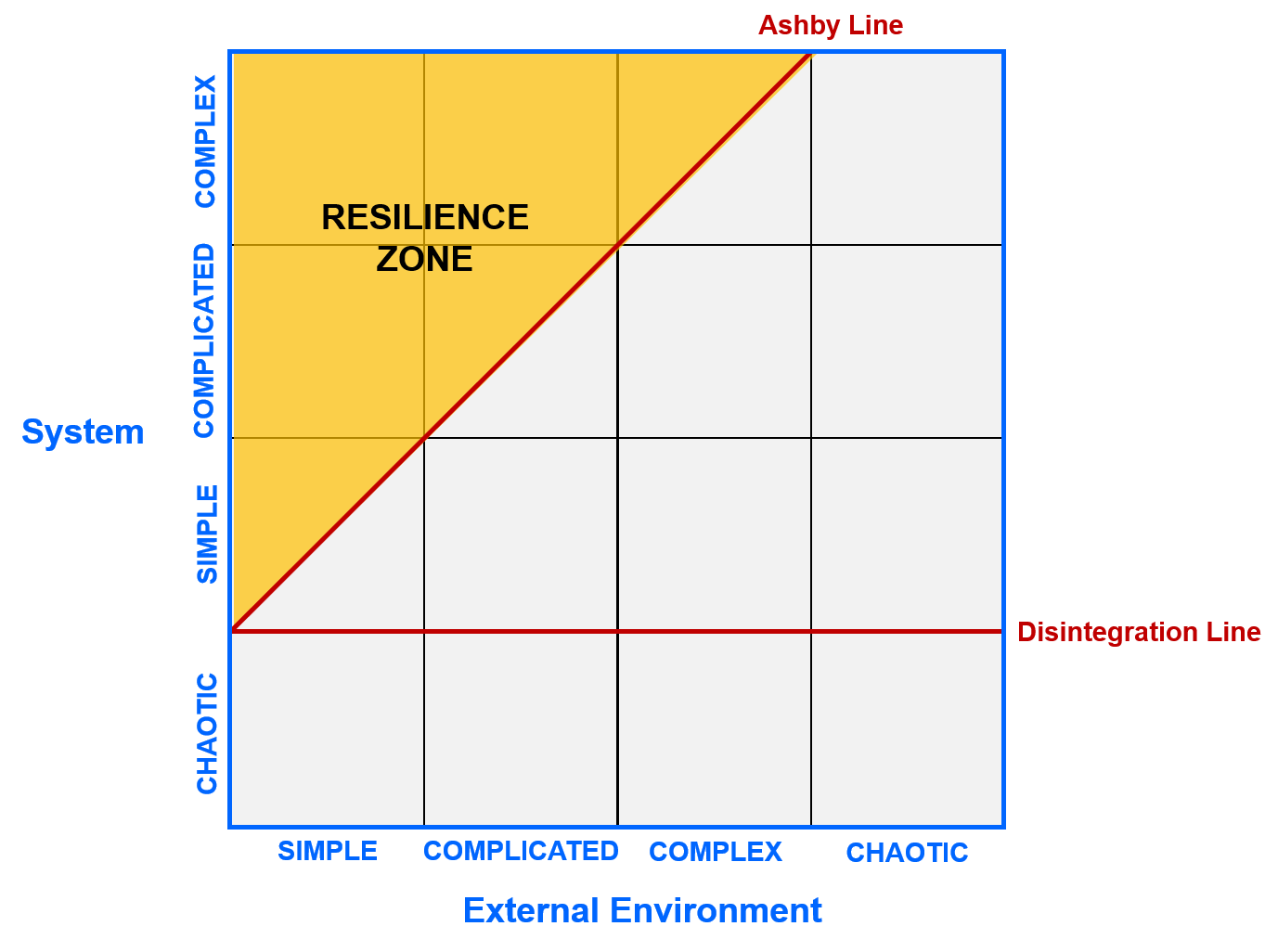

Next, I’ve added another important line onto the graph. This is what I’ve labelled the Ashby Line after cybernetician, W. Ross Ashby, who gave the world a vital first principle way of looking at systems: ‘only variety can absorb variety’. Above the Ashby Line, and my system will be a sustainably resilient one; below the line and I disobey Ashby’s law and hence make myself vulnerable to its consequences.

The idea of this Landscape now is that, assuming I’m able to measure internal and external complexity (and I recognise that’s a big ask… more on which in a subsequent article), I should be able to work out how best to operate, or whether I need to change in order to get into or stay within the Resilient Zone.

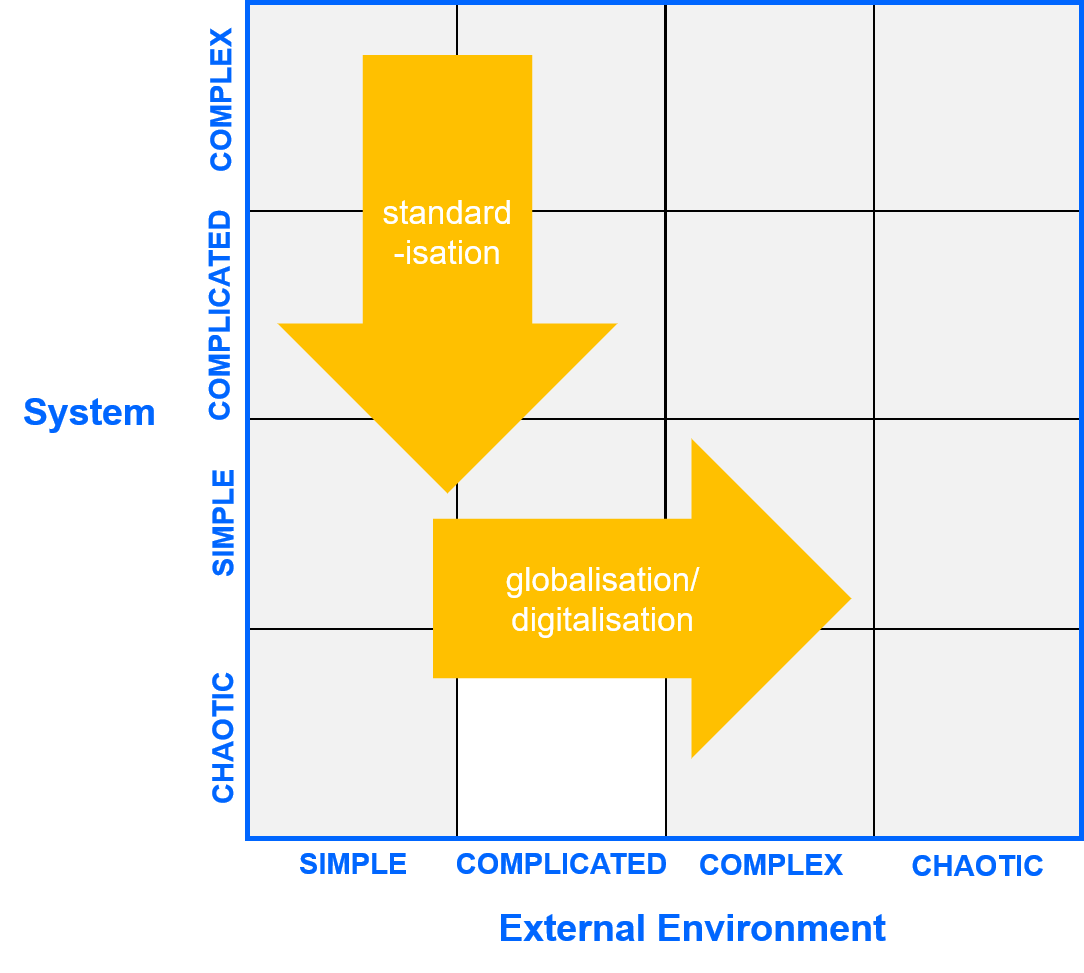

Getting into this Zone, and staying in it is made difficult by two fundamental forces of nature. The first is the downward pull of ‘standardisaton’ as found in most organisations thanks to Lean and SixSigma thinking and their urge to reduce waste and variation. The second then is the increase in external complexity resulting from massive globalisation and digitalisation and resultant speed-of-light feedback loops:

Neither of these forces helps enterprises as a whole. In no small part because, when we look at the Ideal Final Result state of the two different worlds the enterprise has to embrace, there is a fundamental conflict needing to be addressed. In an Ideal world, the Operational Excellence mode of thinking seeks to maximise efficiencies by standardising everything and making life as simple as possible, and for customers (the outside world) to similarly never change its simple existing needs. Workers in the Innovation World mode of thinking on the other hand, knows that they have to embrace complexity if they are to be successful in understanding where in the outside world the next round of paying customer are going to come from and what they are going to demand from providers:

The more I look at this overall model, the more I think I’m going to be writing more about it in the future. Amplifiers and attenuators. Requisite Damping. Variety Flux Index. Understanding the precipice the automotive industry is about to fall off. Understanding Brexit. I filled six pages of notes yesterday afternoon. It might all explode into nothing. Or it might turn out to be the seed of a new Systems Thinking workshop…