The paradox explored in my book ‘The Innovator’s Dilemma’

is that successful companies can fail by making the ‘right’ decisions

in the wrong situations.

Clayton M. Christensen

This year marks the silver anniversary of Clay Christensen’s classic text, The Innovator’s Dilemma, a book that, unlike the vast majority of business titles, is still being referenced twenty-five years after publication.

There was a time during the mid-noughties when I spent a lot of time working with the senior leadership team of an American-headquartered MNC. It felt like they were alternating between me and Professor Christensen: I would be in there one month telling them one thing, and he’d then be in the next month telling them something different. Well, hopefully different. Although, hopefully also, not too different.

In one of those blinding flashes of the obvious that has somehow managed to take fifteen years to arrive, the other day I finally recognised a missing connection between Christensen’s Dilemma and TRIZ. One that, I believe, helps to eliminate some of the criticisms of Christensen’s work. Work that, according to my MNC leaders at least, started with a useful but incomplete theory and gradually, over the remaining course of his career, became increasingly convoluted in an ultimately vain attempt to try and make the theory complete.

For those that aren’t familiar with the Innovator’s Dilemma (full title: ‘When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail’), it works something like this:

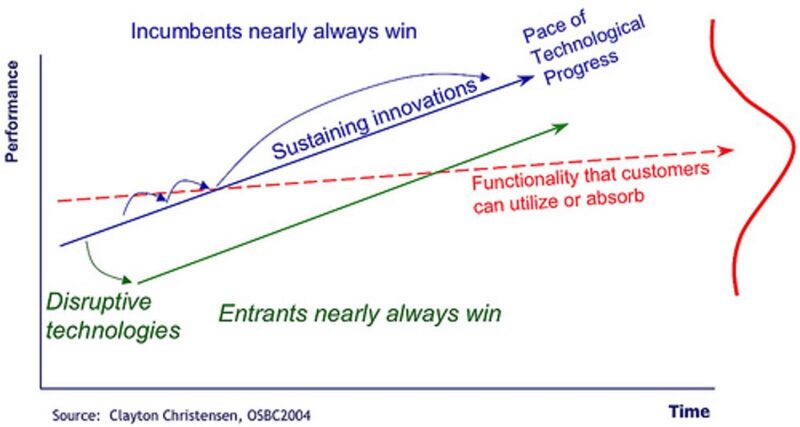

- Someone, often a new player, enters a market with a product or service that has ‘inferior’ performance (and usually lower price) to the existing and established offerings coming from the large incumbent players.

- Because the new offering is ‘inferior’ it attracts the lower end of the incumbents’ customer base. Then, because the incumbent likes the idea of being able to focus on their more profitable higher-end customers, they are inclined to welcome the new player into the market and to take over the hassle and low margins associated with the low-end customers.

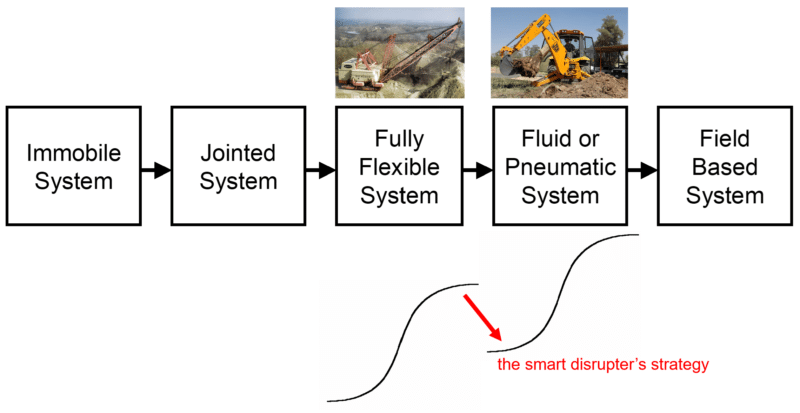

- The entrant improves the likelihood and speed of their future success by identifying a new measure of performance that they can sell to customers alongside their inferior performance against the traditional measures of performance established and being monitored by the incumbent providers (e.g. when hydraulic earth-moving machines first appeared, their earth moving capacity was massively inferior to that of the incumbent cable-driven machines, but they were much more maneuverable; similarly – one of Christensen’s most widely cited case studies – new generation computer disc-drives had inferior memory but offered the benefit of being physically much smaller).

- Engineers and designers, given half an opportunity, will work diligently to improve the performance and value of the products and services under their care. The rate at which they are able to make these improvements tends to be greater than the average rate of increase of customer need. Inside the large incumbent organisation, the engineers focus on meeting the future needs of their highest value customers. For the new entrant engineers, their improvement efforts increasingly attract not just the low-end incumbent customers but also progressively more of the middle and higher end customers. Hence the innovator’s dilemma: incumbents want entrants to take away their least valuable, ‘worst’, customers, but in so doing sow the seeds of the progressive loss of their more valuable customers as the entrant improves their offering. They invite an ‘inferior’ player into the market only for that player to then kill them.

The book was initially written for leaders working in the large incumbent companies. Perhaps ironically, today it more often gets used as a kind of playbook for the so-called ‘inferior’ entrants. And it is from their side that we see the vital missing connection to TRIZ: In the same way that the disrupting entrant makes their journey easier by finding a new performance measure to attract incumbent customers, they can also increase their likelihood and speed of success by following the TRIZ Trends of Evolution:

These trend patterns show engineers, designers and scientists of all industries a clear route-map to more ideal solutions. Prospective market entrants looking for their disruptive ‘inferior’ solutions could choose to find them by looking backwards along the Trends. This would definitely achieve the goal of delivering an ‘inferior’ solution, but it will almost certainly not allow them to win the Innovator’s Dilemma game. To do that they need to recognise that their ‘inferior’ solution needs to be based on forward jumps along at least one of the Trends.

The reason this works is that, because the Trends are built on patterns of successful s-curve jumps: whenever an industry makes a jump from one stage of a Trend to the next, they are effectively jumping from the top of the current curve to the bottom of the next. In such situations, the performance of the new solution will almost inevitably be inferior to the matured old solution. But – crucially – because the Trend pattern has provided us with a roadmap to future success, we can be certain that as the new solution makes its inexorable rise up the new s-curve, it will eventually reach a point where its performance will exceed the maximum capability of incumbent solutions still stuck at the top of the previous s-curve.

The TRIZ Trends in other words serve as the disruptive innovator’s near perfect play-book. Any prospective market entrant can find an ‘inferior’ solution to try and do the job with, but only those using the Trends will be able to identify the ‘inferior’ solutions that will inherently turn into the solution that will dominate the future market once the engineers work their improvement miracles. Good for the new entrants. Less good for incumbents… until we show them a better Innovator’s Solution…