‘What are the most important contradictions?’ A question that comes into the SI Research Team on a regular basis. And one that, perhaps more than any other, warrants the dreaded consultant answer, ‘it depends’. If we’re focusing on tackling climate change, the most important contradictions are different to those we’d select if we were seeking to restore some semblance of trust in the politicians we elect. Or don’t. The answer, too, assuming there is one, also depends on our ability to affect any kind of change, rather than merely working on a problem to achieve the same sort of gratification we get from doing a crossword or playing Wordle. Lots of things – some technical, some business, some psychological – in other words, have an impact on which contradictions we might best spend our time focusing on.

That said, we tried to make a first stab at answering the importance question in the November 2014 SI ezine article, ‘Universal Hierarchy Of Contradictions’. Looking back on that article now, I see two areas of weakness. The first – contradictions associated with morality and ethics – we made a first attempt to address in a much longer article about some of the difficult challenges arising from the Covid pandemic, ‘Covid, Complexity & Contradictions’, that was published in the January 2021 issue of the ezine. The second was the lack of detail at the top of the universal hierarchy, and contradictions associated with the highest level driver, ‘meaning’. Here’s where we get to put a little more flesh on those bones.

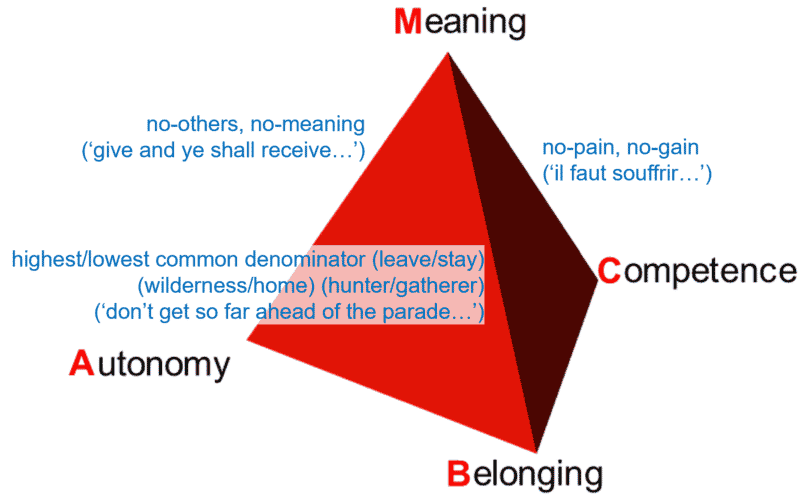

Back in 2014, when it came to our attempts to understand human behaviour at a first principles level, we were talking about the ‘ABC’ model, and the idea that the three primary drivers of human behaviour were our parallel desires for Autonomy, Belonging and Competence. ‘Meaning’, and our innate desire to live lives that are ‘meaningful’, was and still is seen as a higher level principle than ABC, but somewhere between 2014 and today, and with some client projects, the ABC model evolved into the ABC-M model.

The Universal Hierarchy of Contradictions article talked about the inherent conflicts and contradictions between Autonomy, Belonging and Competence, but only peripherally discussed the inherent contradictions that also exist between those three and the higher level Meaning they support. Here, after several years worth of incubation is what we think those three ‘top level’ contradictions look like:

And in a little more detail:

Meaning-Autonomy: meaning only derives from the relationships between things. I might find a particular song or a painting or a book meaningful, for example, but what makes them meaningful are some or a combination of the memories of times with significant others they invoke, or my connection to the songwriter, artist or author, or how what they teach me might enable me to become a better person in the minds of the people around me. Our desire for autonomy and to do what I want to do thus conflicts with the fact that we only derive meaning when we focus on doing right by others.

Meaning-Belonging: being a valued member of the ‘tribe’ has, from an evolutionary perspective, been essential to survival. Activities like eating, sleeping or even just being with others are all meaningful acts. The problem comes when we seek new meaning. That comes only when we leave the safety of the tribe and go explore strange new worlds and have new experiences. And so the fundamental contradiction here is that we need to stay in the tribe and leave it. In line with our oft used John Naisbitt quote, ‘don’t get so far ahead of the parade no-one knows you’re in the parade anymore’, the often impossible challenge for the seeker of the new is how much of it they can hope to bring back to the tribe without being cast out because what they’re saying no longer fits with the values of other tribe members.

Meaning-Competence: the easiest way to ensure we feel competent is to avoid leaving our comfort zone. Learning of any description only really happens when we are prepared to be wrong about things and thus able to acknowledge that we are incompetent. The search for new meaning is again where we experience this contradiction in its most direct form: we need to be both inside and outside our comfort zone. New meaning derives only from our willingness to ‘suffer’ the discomfort of being wrong. Potentially for protracted periods of time. Which pretty much sounds like the core of any innovator’s working day. More on that front in this month’s SI ezine.