Reading Jeff Schmidt’s 2000 book, Disciplined Minds, recently delivered one of those unsettling blinding flashes of the obvious. The sort that make you question, in my case, several decades of assumptions about how the world works. I opened the book as part of a programme of research into leadership, and specifically and attempt to try and understand why all the leaders seem to have disappeared. Schmidt’s addition to the long list of other reasons is that professionals – people I assumed were first and foremost recruited for their subject matter skills – are more likely to be able to build a career as a result of their ideological skills. By which Schmidt means the closeness of match between the ideology of the individual and those of their employer.

If I look at the situation from the employers perspective, they’re paying the professional salaries they pay not just for the technical knowledge that a professional brings, but also on the understanding that they will also comply with the reasons why the enterprise is working on the things they’re working on. The definition of professional, in other words, is someone that does what they’re employed to do, and buy-in to the ideological constraints that their work involves. Speaking as someone that worked for fifteen years in the defence industry, I get it. Designing boundary-pushing jet engines was exciting, but only possible if I either ignored their purpose, or, better, bought into the belief that the work was being done to ensure the future security of the nation.

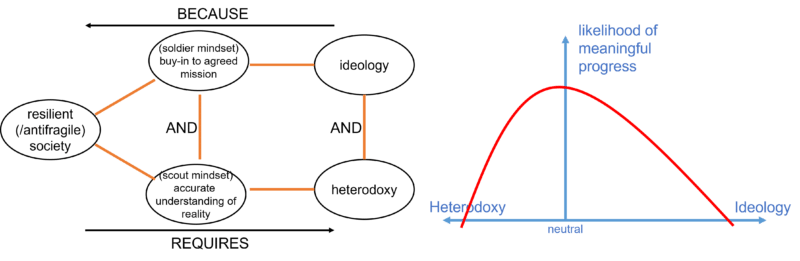

Ideology in this context is a good thing. But like everything else in life, it is possible – nay, inevitable – that at some point you realise that you know have too much of that good thing. Ideology, in other words, offers us yet another example of a Goldilocks Curve: The ideology-based constraints imposed upon professionals are both good and not good.

On the too-much end of the spectrum, (corporate) ideologies are rigid systems of belief that can lead to dogmatism, intolerance, and violence. They are often based on false assumptions and – here’s the kicker – prevent individuals from engaging in critical thinking and considering alternative perspectives. Over-ideologised professionals fail to question their own beliefs and stop being open to changing their minds in light of new evidence. Here’s what an ideology/heterodoxy Goldilocks curve might look like for a typical professional:

The point being that, once we’ve recognised the existence of the contradiction, it is incumbent upon the professional to either manage or transcend it. Managing it in this case largely means understanding where the peak of the curve is in space and time and then doing the best we can to remain at that position. Transcending it, I think, means understanding that all ideology is counter to truth-finding, and that if a person (‘professional’) seeks to be in the change or innovation business, truth-finding is essential. And, moreover, largely emerges through the distillation of the world to meaningful first principles.